Amazing Airmen

Amazing Airmen: Canadian Flyers in the Second World War tells the stories of airmen who fought for Canada during the war or who became Canadians after the war. It is a book about ordeals, and, more particularly, about surviving ordeals.

Those who survived often had to overcome incredible obstacles to do so — dodging bullets and enemy troops, escaping from burning planes and enduring forced marches if they became prisoners. The ability of the veterans to survive their ordeals was so miraculous that these stories may seem more like fictional accounts than what they are: non-fiction stories.

In one story, a tail gunner from Montreal survived despite being unconscious when blown out of his bomber. Another story describes how the crew of a navigator from Ottawa used chewing gum to fill holes in their aircraft. Another tells how a pilot from Northern Ontario parachuted out of his plane and became the target of a German machine-gunner, but within hours 120 Germans surrendered to him.

These painstakingly researched stories will enable you to feel what the veterans endured when they were young men during the war.

Those who survived often had to overcome incredible obstacles to do so — dodging bullets and enemy troops, escaping from burning planes and enduring forced marches if they became prisoners. The ability of the veterans to survive their ordeals was so miraculous that these stories may seem more like fictional accounts than what they are: non-fiction stories.

In one story, a tail gunner from Montreal survived despite being unconscious when blown out of his bomber. Another story describes how the crew of a navigator from Ottawa used chewing gum to fill holes in their aircraft. Another tells how a pilot from Northern Ontario parachuted out of his plane and became the target of a German machine-gunner, but within hours 120 Germans surrendered to him.

These painstakingly researched stories will enable you to feel what the veterans endured when they were young men during the war.

Comments on Amazing Airmen

"On the occasion of your official launch my congratulations on this fine work. Your interviews and tales are graphic and concise. And they are of great value in preserving the history of my generation in the air over Europe during WWII." Major-General Richard Rohmer

"After I started reading Amazing Airmen, my wife became annoyed with me because I wouldn’t turn the lights out and go to bed. I couldn’t put the book down because it’s extraordinary.” Gord Ferguson, pilot officer (retired), Royal Canadian Air Force

"From beginning to end, Amazing Airmen truly chronicles the bravery and sacrifices made by RCAF airmen during the Second World War. 5 stars." Rick Thomson

"There are so many unforgettable stories in Amazing Airmen that it is impossible to tell all of them here. Deftly combining interviews with veterans, archival sources and earlier histories, Darling accomplishes an impressive feat with this work: He humanizes the airmen in a way that the reader can instantly connect with them. Best of all, Darling is a master storyteller who allows the drama to unfold at a riveting pace in each chapter.

"I've chosen to spotlight Darling's book because it shows how one individual with a deep love of history can bring the past to life. By telling the stories of the veterans in such a gripping and poignant way, Darling's Amazing Airmen keeps the memory of these brave veterans alive." Andrew Hunt, associate professor of history at the University of Waterloo, in a column in the Waterloo Region Record, November 10, 2009

"After I started reading Amazing Airmen, my wife became annoyed with me because I wouldn’t turn the lights out and go to bed. I couldn’t put the book down because it’s extraordinary.” Gord Ferguson, pilot officer (retired), Royal Canadian Air Force

"From beginning to end, Amazing Airmen truly chronicles the bravery and sacrifices made by RCAF airmen during the Second World War. 5 stars." Rick Thomson

"There are so many unforgettable stories in Amazing Airmen that it is impossible to tell all of them here. Deftly combining interviews with veterans, archival sources and earlier histories, Darling accomplishes an impressive feat with this work: He humanizes the airmen in a way that the reader can instantly connect with them. Best of all, Darling is a master storyteller who allows the drama to unfold at a riveting pace in each chapter.

"I've chosen to spotlight Darling's book because it shows how one individual with a deep love of history can bring the past to life. By telling the stories of the veterans in such a gripping and poignant way, Darling's Amazing Airmen keeps the memory of these brave veterans alive." Andrew Hunt, associate professor of history at the University of Waterloo, in a column in the Waterloo Region Record, November 10, 2009

The Man Who Fell To Earth — And Lived

This condensed version of a chapter in Amazing Airmen appeared in the Toronto Star on April 7, 2007.

|

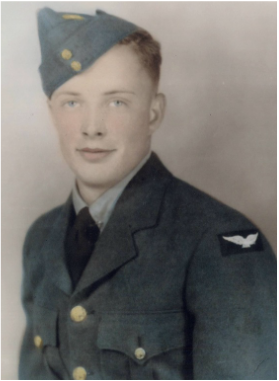

Harry Denison during the Second World War.

|

As Flight Sgt. Harry Denison settled into the gun turret of Halifax bomber NP799 on March 5, 1945, he heard that the plane that had taken off ahead of him had crashed. Ice may have formed on its wings.

It was a cold, misty night at the air base at Linton-on-Ouse in Yorkshire, England. Despite the weather, Denison's pilot, Flight Lieut. Jack Kirkpatrick, rolled the Halifax down the tarmac runway after the crew had checked their equipment. Denison, a farm boy who grew up near Vernon, B.C., checked to make sure his parachute was strapped to the plane's fuselage near his turret.

Kirkpatrick, Denison and the rest of the crew were with the Royal Canadian Air Force's 426 Squadron. That night, they were flying to Chemnitz, an industrial city in eastern Germany.

As NP799 left England, the weather improved. Denison looked out of the dome above his turret in the middle of the plane. He was watching for German night fighters.

It was a routine flight, until, suddenly, Denison heard an explosion. Something hit the plane. The dome above the gun turret was damaged. A piece of the heavy plastic in the dome fell onto Denison's head, cutting him from his right ear to his chin.

Bleeding profusely, Denison slipped out of his turret seat and dropped to the floor. He wanted to get his parachute and attach it to his harness, which he was wearing.

Denison didn't know what had caused the explosion. He didn't know if a night fighter had fired on the bomber or whether another bomber had accidentally collided with NP799. He also didn't know that the plane was completely breaking up. He was rapidly descending in the centre section of the bomber's fuselage.

Denison was completely immobile. As the bomber hurtled toward the ground, the inertial forces pinned him to the fuselage floor so that he couldn't reach his parachute.

He thought about his crew: Kirkpatrick, the pilot; Sgt. Ian Giles, the flight engineer; Flying Officer Bob Fennell, the navigator; Flying Officer Bud Stillinger, the bomb-aimer; Pilot Officer Jack Larson, the wireless operator; and Pilot Officer Roald Gunderson, the tailgunner. Were they still alive? Denison couldn't see or hear any of them.

Then, he thought of his family: his father, Norman, and mother, Ethyl. How would they feel when they learned that their son had been killed?

After the fuselage came crashing down, Denison lay unconscious on the floor near the turret for seven or eight hours. Snow swirled around him.

When the sun came up, Denison slowly regained consciousness. His entire body was bruised. Denison crawled outside. He was in a pine forest west of Chemnitz.

He looked for his crewmates, but couldn't see them. In fact, he couldn't see much of NP799. He could see only the section of the fuselage in which he had been trapped. The nose, cockpit, tail and the two wings had become separated from the fuselage some time after the explosion.

Later that morning, Denison wandered along a trail and found a stream. He wanted to drink from it. He was so weak, however, that he collapsed into the stream and had to pull himself out.

He thought he was alone, but then he heard noises. He screamed for help.

Some men wearing grey pyjama-like uniforms approached. They were slave labourers who were cutting wood. They carried him to their base, which was a German army camp. The commanding officer took Denison to a nearby hospital where German doctors treated his head wound and a broken rib.

When the hospital released Denison, a guard escorted him on a train to an interrogation camp at Frankfurt. After a few days, he was taken to Dulag Luft III, a prisoner-of-war camp near Nuremberg.

In early April, after Denison had been at Dulag Luft III about a week, the German troops at the camp told the prisoners to pack their belongings. They were going on a forced march.

The Allies were pressing on all fronts, and Germany's leaders were getting worried. German authorities wanted to move the prisoners away from the Allies so that they could be used as hostages during any peace negotiations that occurred.

Still limping, Denison started walking through the German countryside in wet, miserable weather.

Some of the prisoners were exhausted. Others were so sick with illnesses such as dysentery that they stopped walking. German guards used their rifle butts to encourage the prisoners to keep marching.

While on their march, Denison and his fellow prisoners were taken to a railway siding and herded onto open rail cars such as might have been used to carry gravel.

Suddenly, the prisoners heard planes coming toward them. There were a total of 17 aircraft, and they were flying fast and low. The planes were American fighters.

Denison ran from the train as quickly as he could. He got about 100 metres away and started looking for any kind of shelter. He fell into a ditch. The planes dropped bombs on the train and then, moments later, came back firing cannon shells. Denison felt something warm hit his head. It was an empty shell case.

German troops on two flatbed rail cars fired anti-aircraft guns at the planes, but the fighters destroyed the train, killing the gun crews. From then on, Denison and the other prisoners insisted they travel only on roads.

The prisoners scrounged food such as potatoes and sugar beets, and they slept wherever they could. One evening, Denison slept in a barn next to a family of pigs.

After marching for 17 days, the prisoners arrived at Stalag VIIA, which was near Munich.

On Sunday, May 6, the prisoners woke up to find the German guards had left. They had fled in advance of the arrival of American troops.

Denison soon flew back to England. At Bournemouth, he sent a telegram to his parents to tell them he was alive. Until then, they knew only that he was missing.

Denison returned to Canada on the ocean liner Ile de France. When he arrived at Halifax, he boarded a train with other servicemen who had been prisoners of war. He got off the main train at Sicamous, B.C., and boarded another train for Vernon, where his family met him.

Years later, Denison learned that the bodies of all the members of his crew except Giles were found in Germany and buried at a military cemetery near Berlin. Giles, the flight engineer, remains unaccounted for.

Denison left the military to work on the family farm, later going into construction and the transportation field. He lives today in a home near North Bay, overlooking Lake Nipissing.

He still wonders about the cause of the explosion and suspects that an Allied plane collided with NP799. He thinks his crew would have spotted a night fighter.

Denison, now 82, drives around North Bay with a small reminder of his ordeal. The licence plate on his forest-green Toyota van contains the letters "NO CHUT." It sums up how he fell from the sky above Germany.

It was a cold, misty night at the air base at Linton-on-Ouse in Yorkshire, England. Despite the weather, Denison's pilot, Flight Lieut. Jack Kirkpatrick, rolled the Halifax down the tarmac runway after the crew had checked their equipment. Denison, a farm boy who grew up near Vernon, B.C., checked to make sure his parachute was strapped to the plane's fuselage near his turret.

Kirkpatrick, Denison and the rest of the crew were with the Royal Canadian Air Force's 426 Squadron. That night, they were flying to Chemnitz, an industrial city in eastern Germany.

As NP799 left England, the weather improved. Denison looked out of the dome above his turret in the middle of the plane. He was watching for German night fighters.

It was a routine flight, until, suddenly, Denison heard an explosion. Something hit the plane. The dome above the gun turret was damaged. A piece of the heavy plastic in the dome fell onto Denison's head, cutting him from his right ear to his chin.

Bleeding profusely, Denison slipped out of his turret seat and dropped to the floor. He wanted to get his parachute and attach it to his harness, which he was wearing.

Denison didn't know what had caused the explosion. He didn't know if a night fighter had fired on the bomber or whether another bomber had accidentally collided with NP799. He also didn't know that the plane was completely breaking up. He was rapidly descending in the centre section of the bomber's fuselage.

Denison was completely immobile. As the bomber hurtled toward the ground, the inertial forces pinned him to the fuselage floor so that he couldn't reach his parachute.

He thought about his crew: Kirkpatrick, the pilot; Sgt. Ian Giles, the flight engineer; Flying Officer Bob Fennell, the navigator; Flying Officer Bud Stillinger, the bomb-aimer; Pilot Officer Jack Larson, the wireless operator; and Pilot Officer Roald Gunderson, the tailgunner. Were they still alive? Denison couldn't see or hear any of them.

Then, he thought of his family: his father, Norman, and mother, Ethyl. How would they feel when they learned that their son had been killed?

After the fuselage came crashing down, Denison lay unconscious on the floor near the turret for seven or eight hours. Snow swirled around him.

When the sun came up, Denison slowly regained consciousness. His entire body was bruised. Denison crawled outside. He was in a pine forest west of Chemnitz.

He looked for his crewmates, but couldn't see them. In fact, he couldn't see much of NP799. He could see only the section of the fuselage in which he had been trapped. The nose, cockpit, tail and the two wings had become separated from the fuselage some time after the explosion.

Later that morning, Denison wandered along a trail and found a stream. He wanted to drink from it. He was so weak, however, that he collapsed into the stream and had to pull himself out.

He thought he was alone, but then he heard noises. He screamed for help.

Some men wearing grey pyjama-like uniforms approached. They were slave labourers who were cutting wood. They carried him to their base, which was a German army camp. The commanding officer took Denison to a nearby hospital where German doctors treated his head wound and a broken rib.

When the hospital released Denison, a guard escorted him on a train to an interrogation camp at Frankfurt. After a few days, he was taken to Dulag Luft III, a prisoner-of-war camp near Nuremberg.

In early April, after Denison had been at Dulag Luft III about a week, the German troops at the camp told the prisoners to pack their belongings. They were going on a forced march.

The Allies were pressing on all fronts, and Germany's leaders were getting worried. German authorities wanted to move the prisoners away from the Allies so that they could be used as hostages during any peace negotiations that occurred.

Still limping, Denison started walking through the German countryside in wet, miserable weather.

Some of the prisoners were exhausted. Others were so sick with illnesses such as dysentery that they stopped walking. German guards used their rifle butts to encourage the prisoners to keep marching.

While on their march, Denison and his fellow prisoners were taken to a railway siding and herded onto open rail cars such as might have been used to carry gravel.

Suddenly, the prisoners heard planes coming toward them. There were a total of 17 aircraft, and they were flying fast and low. The planes were American fighters.

Denison ran from the train as quickly as he could. He got about 100 metres away and started looking for any kind of shelter. He fell into a ditch. The planes dropped bombs on the train and then, moments later, came back firing cannon shells. Denison felt something warm hit his head. It was an empty shell case.

German troops on two flatbed rail cars fired anti-aircraft guns at the planes, but the fighters destroyed the train, killing the gun crews. From then on, Denison and the other prisoners insisted they travel only on roads.

The prisoners scrounged food such as potatoes and sugar beets, and they slept wherever they could. One evening, Denison slept in a barn next to a family of pigs.

After marching for 17 days, the prisoners arrived at Stalag VIIA, which was near Munich.

On Sunday, May 6, the prisoners woke up to find the German guards had left. They had fled in advance of the arrival of American troops.

Denison soon flew back to England. At Bournemouth, he sent a telegram to his parents to tell them he was alive. Until then, they knew only that he was missing.

Denison returned to Canada on the ocean liner Ile de France. When he arrived at Halifax, he boarded a train with other servicemen who had been prisoners of war. He got off the main train at Sicamous, B.C., and boarded another train for Vernon, where his family met him.

Years later, Denison learned that the bodies of all the members of his crew except Giles were found in Germany and buried at a military cemetery near Berlin. Giles, the flight engineer, remains unaccounted for.

Denison left the military to work on the family farm, later going into construction and the transportation field. He lives today in a home near North Bay, overlooking Lake Nipissing.

He still wonders about the cause of the explosion and suspects that an Allied plane collided with NP799. He thinks his crew would have spotted a night fighter.

Denison, now 82, drives around North Bay with a small reminder of his ordeal. The licence plate on his forest-green Toyota van contains the letters "NO CHUT." It sums up how he fell from the sky above Germany.

|

Harry Denison stands beside his van with the licence plate NO CHUT, which sums up how he descended from the sky above Germany. Photo courtesy of Art Fraser.

|

Two German researchers learned about Harry Denison's flight when they read Ian's story in the Toronto Star on the internet. They knew the crash site and sent several pieces of Harry's plane to Ian to give to Harry.